To Exoticize

Lately, I’ve been plagued with the constant anxiety of what it means to make images in a place that one does not fully understand. The idea of a ‘tourist image’ fosters a foundation of doublethink; to make a tourist image is to capture a picture of a place traveled to that is not home, while, at the same time, capturing a perspective of that place that is not necessarily true to that place. I do genuinely believe that to make beautiful and wholistic images of a place one must understand and have studied that place, however, that is then to say that it is impossible to make an image of the same characteristics of a place unknown.

This week I will explore the ways in which photographers have exoticized, exploited, saturated, and utilized other cultures, peoples, and places for the benefit of themselves, their culture, or even their colonialism.

Pierre Dieulefils and Rigal, 1892

To ‘postcard’ is most-definitely to exoticize. These images were all part of a collection made in central and northern Vietnam and represent a “touched-up version […] for the western perspective“ according to Saigoneer.

Be it the tools, techniques, religious and spiritual practices, food, clothing, art, or musical instruments, each of these images exploits an aspect of culture thought to be considered ‘interesting’ by a common westerner.

Northcote Thomas’ Questionable Photography

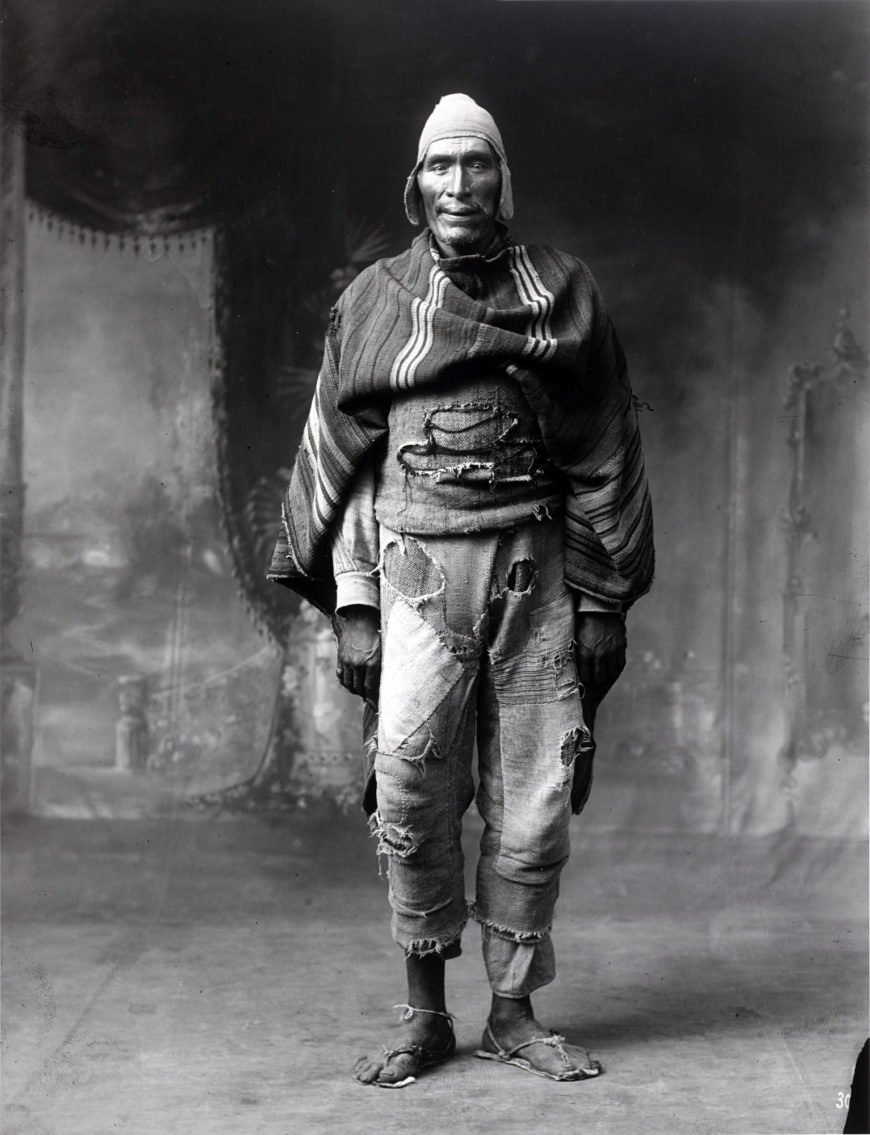

Here we witness how the camera was (and still very much is) used as a means of studying, labeling, and profiling people based on the horrendous consequences of the colonial gaze.

“Since Western culture and the Caucasian racial type were positioned as the pinnacle of social evolution, photography in this period remained almost exclusively in the hands of Caucasian scientists and anthropologists who would use photography as a medium to validate their own beliefs and disseminate racist tropes.”

Cameras were used in conjunction with other shallow means of understanding differences in humans based on irreparable and false correlations of the physique to species. Type photographs, “often emphasizing corporal features such as cranium size to propose a correlation between physical type and intelligence, even going as far as suggesting a propensity towards criminal behavior” have caused immense harm to cultures and peoples that can never be undone. When rebutting these arguments, this author mentions

“what originated as a tool for scientific racism, can transfigure into a profound visual memoir offering a unique insight into ancestral heritage depending on who it is viewed by.”

“A metaphor used by French philosopher Michel Foucault to explore ideas surrounding power and surveillance, the Panopticon is a circular prison with a centralised watchtower from which a guard can see every prison cell. Today the camera takes the place of the guard's all-seeing eye playing a central role in the facilitation of corporate and governmental power. When we examine the history of the camera it becomes abundantly clear that this is not a new role it has inhabited, but rather a position it has filled for decades.”

Martín Chambi

Chambi represents a very unique perspective on this topic. Born and raised in impoverished Peru, Chambi has the unmatched ability to capture and make images of his own people while utilizing technique and skillsets acquired and learned from British photographers.

“Chambi created these pictures of Sihuana at his own initiative and expense—they were not commissioned portraits. He did not make much money off of the images after they were created either. Chambi’s photograph was originally published in the Lima-based newspaper El Peruano in the article “The Giant of Paruro?”, but it was not printed on postcards, displayed in exhibitions, or published in additional formats during Chambi’s lifetime. The photograph’s limited circulation may indicate Chambi’s rejection of historical narratives that exoticized and “othered” native Peruvians. Since the early colonial period, European writings and illustrations produced in and about Peru had treated its Indigenous populations derisively. At best, Indigenous people were portrayed as innocents incapable of self-governance; at worst, they were dehumanized as devil-worshiping heathens in need of conversion and control.”

Whereas Chmbi’s mentor intentionally withheld the names of his sitters as to represent them as merely representational of the lower strata of the socio-economic groups of the culture, along with the utilization of the image, again, on the back of a postcard.

Pushpamala

“Pushpamala, a contemporary Indian artist, challenges colonial photography and exposes the anachronistic portrayal of history by transforming herself into both the exoticized ‘native’ and the anthropologist, thereby subverting and undermining the colonial gaze in a critical and satirical manner.”

“Anthropological photographs serve as evidence of how colonizers asserted their powers and primordial racial superiority by depicting 'savages' and othering them in the process. Maurice Vidal Portman, a self-proclaimed historian and anthropological photographer who identified himself as the father of the Andamans, exemplifies this fixation and construction of 'savages' through documentation and photography for scientific insight as an outsider.”

Pushpamala N. Toda, From the Ethnographic Series Native Women of South India: Manners & Customs, 2000-2004

“The ‘native’s’ subordinate position is shown through her crouching position lower than those controlling the setting, thereby exposing the exploitative nature of anthropologists. The use of a dull backdrop in Figure 3 and 4 removes and displaces the 'native' from the natural context to emphasize physical features whilst ironically adding 'natural' props such as foliage to recreate the setting evident in Portman’s process.”